Allegations of Bias of the International Criminal Court Against Africa: What Do Kenyans Believe?

In 2020, a group of international experts will review the work of the International Criminal Court (ICC). After nearly two decades of operations, one issue that the experts should consider is what victims of atrocities think of the ICC’s work.

Some African leaders have accused the ICC of being biased against their continent. Pointing to the fact that a majority of investigations are for situations in African countries, they complain that, in its first two decades, the ICC engaged in selective justice, infringing on sovereignty in post-colonial states. Some experts counter that the ICC simply opened investigations in the situations of gravest concern, where the most people died in atrocities.

Whether the Court is in truth biased, perceptions matter. What do Africans, and specifically victims of mass atrocities, think about whether the ICC is biased against Africans?

In a new paper published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, we and Tessa Alleblas answer this question using data from Kenya. We find that those exposed to political violence are much less likely to hold negative attitudes about the ICC. Before explaining in greater detail, some background is in order.

Kenya is a critical case because it is normally deemed to be a failure of international criminal justice. Following a disputed 2007 election, horrific violence engulfed Kenya. Perpetrators killed over 1,100 people, committed horrific sexual violence, destroyed property, and displaced more than half a million inhabitants. The ICC charged rival political leaders Uhuru Kenyatta (a Kikuyu) and William Ruto (a Kalenjin) for that violence. Allegedly, these leaders set their supporters against one another, overseeing the commission of international crimes for political gain.

This was the first time that the ICC head prosecutor used independent proprio motu powers, which allow the prosecutor to open a preliminary examination without a state or UN Security Council referral.

In response, Kenyatta and Ruto decided to fight the charges on the political stage. Unexpectedly, the two former enemies united to run for president and vice president respectively in 2013. After winning, they attacked witnesses and savaged the ICC in public. The proceedings against them would ultimately be suspended by 2016.

Kenyatta, Ruto, and their supporters treated this as vindication, and as a victory against ICC bias. Many presume that this sentiment is shared by Kenyans and other Africans. But we actually know very little about what drives perceptions of ICC bias in African countries, especially Kenya.

To learn more, in October 2015, we and a team of researchers collected data from 507 Kenyans seeking answers to this and other questions related to perceptions of the ICC.

The evidence is compelling. We find that those who suffered or witnessed post-election violence are far less likely than others to believe that the ICC is biased against Africans. This suggests that those for whom the ICC was originally established – victims of mass atrocities – are the least likely to offer negative assessments of the Court.

The effect of exposure to violence is large: the odds that a person agrees with the statement “The International Criminal Court, ICC, or The Hague is biased against Africa” are nearly three times lower if one self-identifies as a victim or witness of post-election violence.

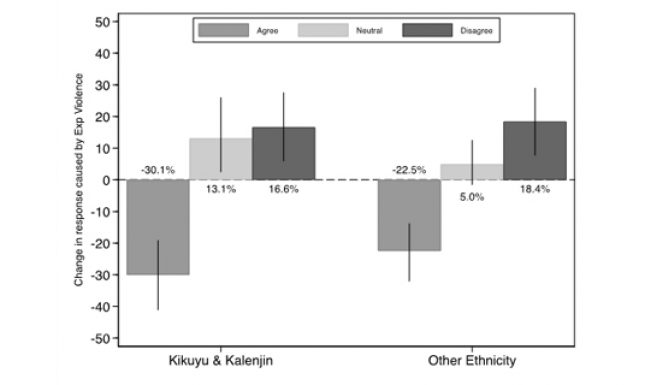

To be sure, politics and identity still matter. Respondents who self-identify as co-ethnics of Kenyatta and Ruto are much more likely to view the ICC as biased compared to those from other ethnic groups. However, exposure to violence has a more pronounced effect on attitudes among the leaders’ co-ethnics. Kikuyu and Kalenjin respondents who were exposed to violence are 30% less likely to agree that the ICC is biased, compared to only 22.5% in other groups.

What this means is that exposure to violence challenges one’s acceptance of ethnic group attitudes.

What does this mean for the hope of international criminal justice? First, at least in Kenya, exposure to violence apparently neutralizes some negative perceptions of the ICC. Second, ethnicity does not always trump other factors when individuals form opinions of the ICC.

Our data suggest that those who the ICC aimed to primarily serve, the victims of mass atrocities, will maintain attitudes that differ substantially from their ethnic groups. If the ICC wants to avoid failures like those that occurred in the Kenyatta and Ruto cases, it might do well to amplify the voices of victims.