Dealing with Fake News: An Absolute Necessity, but How?

In today’s digitized society, we witness an ‘anarchy’ of data and information coming from a myriad of sources. Parts of it can be classified as ‘fake news’ but how can you distinguish real from fake?

The term ‘fake news’ has been around since at least the 1970s, and more recently became famous when a US President used it to discredit all information that was not beneficial to him. Meanwhile social media helps invented stories to go viral, while articles from reputable sources are called “fake news” by those who see them as hostile to their agenda.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has shown even more troublesome effects of ‘fake news’. However, how can you distinguish truthful information from untruthful information?

Intelligence agencies have been dealing with the problem of fake news, or in jargon ‘mis- and disinformation’, basically since their creation. Their opponents usually try to hide their intentions and capabilities by tricks of denial and deception, leaving intelligence agencies to sift through mountains of data and information, determining what is real and what is ‘fake’.

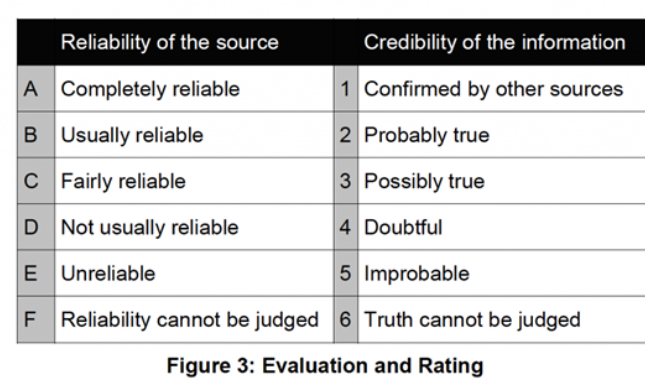

To support that task, Western military and intelligence agencies use so-called grading or evaluation systems which assign a value to the reliability of the source and a value to the probability of the information as being correct.

These systems are based on the so-called ‘Admiralty System’ or ‘Admiralty Code’. This system has its origin in the practices of the British Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division. When in 1939, at the brink of the Second World War, a new Director of Naval Intelligence arrived, he found the anarchy of different information reports without a clear indication of their value, ‘intolerable’ (from Room 39, D. McLachlan 1968, p.22)

A new method was introduced in which the source and the information itself were evaluated separately, coding the evaluation with letters and numbers from “A1” to “D5”. The letter indicates the degree of credibility of the source, and the number represents the probability of the information as being correct.

The reason for separating source evaluation from the evaluation of the information itself, was that after all, it is possible that valuable information may come from a source with a bad reputation and, conversely, disinformation may come from a source which is usually reliable. To show how the evaluation of a source works, McLachlan quotes in his book (p. 23) an officer involved in devising the system:

“A good source in some hospital in Brest might be graded “A” as to the number killed and wounded in an air attack, but might be a “C” source on the extent of mechanical damage caused to a ship in the dockyard. An equally good source in the Port’s Chaplain office who had seen the ships defect list, might be “A” on damage caused, but “C” on the number killed and wounded. A very junior engine-room rating taken prisoner and speaking in good faith may be an “A” or “B” source on the particulars of the engine of which he is in charge, but will be “C”, “D”, or even “E” on the intended area of operations of the U-boat in which he served.”

This quote shows that ‘credibility’ represents more than just truthfulness; it also takes the competence of the source on the subject of the information into account. Translated to a modern context: any source without proven relevant medical knowledge who is sharing information about a medicine supposedly effective against COVID-19 receives low credibility in this system.

Assigning value to the probability of the information is a more difficult task and usually requires knowledge on the topic, although healthy scepticism is already helpful as well.

The grading system, which is often still referred to as the Admiralty System, has evolved, and, for example, the current NATO standard includes 6 different grades for the reliability of the source (A-F) and 6 grades to indicated the credibility of the information (1-6).

While researchers to a large extent (although not blindly) can rely on the system of peer-review to prevent ‘fake news’ from entering academic publications, this is different when it comes to information on social media. There ‘fake news’ is floating around abundantly so putting the principles behind the Admiralty Code to practice is probably even more relevant today than ever before. Not only for intelligence services, but for everyone.

Starting with a review of the trustworthiness and certainly also of the competence of the source on the specific topic by asking ‘why do they share this?’ and ‘do they know what they’re talking about?’, will help to identify most of the malign and – more common – incompetent sources. So does a source sharing information on, for example vaccines, have any medical background him/herself? If not, you may want to look for a more credible source if you’re interested in the topic.

And by doing so, very likely you could weed out most of the ‘fake news’ before it reaches you, which will also prove to be a great time saver. As a result, more time can be devoted to information from credible sources, of course still with a healthy dose of scepticism.