Islamic State’s Ambivalent Relation to Drugs

According to Islamic State’s official propaganda – as stated in its Dabiq-magazine – it is very anti-drugs. However, in practice, Islamic State seems to use drugs to make money and strengthen its fighters. How to explain this ambivalence?

Islamic State (IS) appears to have an ambivalent stance towards drugs. According to IS’ official propaganda – as stated in its Dabiq-magazine – it is very anti-drugs. However, in practice, IS seems to use drugs to make money and strengthen its fighters. How to explain this ambivalence?

Linking terrorism to drugs

A 2014 social network analysis among 2,739 people involved in international smuggling, indicates a correlation between drugs and terrorism. The researchers found ‘some reasonable level of integration between the criminal and terrorist elements operating globally.’ (p. 80) Discussions on the link between terrorism and drugs often seem focused on drugs trade enabling terrorism. Terrorism and drugs trade are oftentimes referred to as ‘narco-terrorism,’ a contested concept by itself. Typically, there are five mechanisms through which drugs contribute to terrorism: ‘supplying cash, creating chaos and instability, supporting corruption, providing “cover” and sustaining common infrastructures for illicit activity, and competing for law enforcement and intelligence attention,’ adding that ‘cash and chaos are likely to be the two most important.’ In 2008, sixty percent of terrorist organizations were believed to be involved in drugs trafficking.

IS’relation to drugs

IS however, actually claims to fight against drugs. In its online magazine Dabiq it frequently points at arrests being made of drugs traffickers. When going through the thirteen editions of Dabiq up to the moment of writing, the word ‘drugs’ is used on seven occasions. In all these cases, ‘drugs’ is used in a negative connotation. The word ‘drug’ appears in Dabiq two and twelve in the same contexts. Synonyms like ‘narco’, or specific drugs like ‘heroin’, ‘amphetamine’, and ‘Captagon’ do not appear.

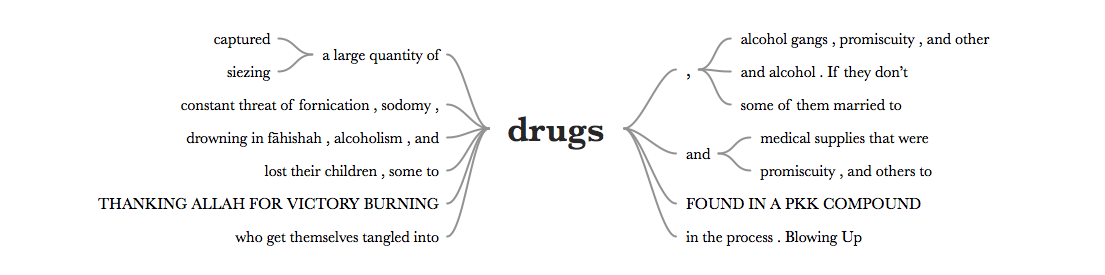

Figure: Wordtree resulting from analysis of Dabiq editions one to thirteen on the word ‘drugs’, which occurred seven times in the magazine.

IS’ behavior with respect to drugs is ambivalent. IS seems to have destroyed a heroin shipment of the Mexican Sinaloa cartel, taking over its heroin production and routes. IS allegedly earned over $1 billion with heroin and synthetic drugs. Also, its fighters use such drugs to stay awake much longer. The challenge with analyzing the actual behavior is that it is oftentimes incorporated within a message, especially in the case of IS where researchers have to rely mainly on secondary sources. As such it contributes to disinformation and manipulation; for example, the threats of Sinaloa cartel leader ‘El Chapo’ appear a hoax. Nevertheless, there seems a gap between IS’ anti-drugs narrative and its actual behavior.

Explaining IS’ ambivalence to drugs

So, how to explain that gap? Referring to three models identified by Graham Allison to analyze foreign policy, three explanations might provide insight in this ambivalence. First, IS tries to benefit from drugs and drugs trade, masking its intentions by anti-drugs rhetoric. A second explanation focuses on different, contrary policies among IS’ governing committees; for example, while the military or financial committees might see benefits, ideological committees might oppose use of drugs. According to a third explanation, IS’ official policy is anti-drugs, but certain individuals do not oblige by the rules for personal, financial gains. While the assumed high level of control within IS-society might make this unlikely, it cannot be ruled out completely.

So, although it seems IS’ statements and behavior are opposing (first explanation), this does not necessarily have to be so (second and third explanations). The very ambivalence in the first explanation might be used in a counter-narrative against Islamic State, claiming that it pretends to follow strict religious rules on drugs, but that it actually does not. The second explanation’s competition among different governing committees over policies (for example the financial and military versus the ideological committees) might lead to fragmentation from within, resembling an approach to contain Islamic State to obtain fragmentation. Following the third explanation, a counter-narrative might be beneficial as well, exposing IS’ weakness to control its territory.