Licensed Detection Agents: A New Approach to Financial Crime

We are failing to detect money laundering, market manipulation, and other financial crimes. In a research paper, selected to be featured at DC Fintech Week 2024, I propose a new solution: Licensed Detection Agents.

We often think of crime in binary terms. Cops versus criminals. Sheriffs versus outlaws. Tom Hanks versus Leonardo DiCaprio in Catch Me if You Can. But reality is far more complex when it comes to financial crime. The key to identifying money laundering, market manipulation, and other schemes is to spot suspicious transactional patterns. But the state generally cannot monitor our every financial move. Instead, they have outsourced the detection of financial crime to the private sector. Banks and other financial institutions are legally required to surveil their own customers and, where necessary, report suspicious activity. We refer to these private actors as the “gatekeepers” of the financial system.

Unfortunately, however, evidence suggests that gatekeeper models for financial crime detection are not working. This is not for want of investment; gatekeepers spend more than $200 billion per year on their financial crime controls. This includes personnel costs, as exemplified by the Netherlands where 20% of the banking workforce is fully dedicated to Anti-Money Laundering (AML) compliance. Nevertheless, our best available estimates suggest less than 1% of global money laundering is detected. The situation is even worse when it comes to insider trading and market manipulation. One study estimates, for example, that we fail to detect approximately 99.7% of ‘closing price manipulation’ – just one of many forms.

There are numerous contributing factors to these low detection rates. Spotting financial crime is not easy, particularly when sophisticated criminals – including state-back groups – spread their activity across multiple financial institutions. The rules governing gatekeeper obligations can also be unclear. And, in some cases, regulators may lack the resources necessary to chase down legitimate reports of suspicious activity.

But the primary impediment is neither resource constraints nor technical complexity. Rather, it is the misaligned incentives of the gatekeeper model. The fundamental problem is that it relies on private firms to monitor their own customers. Virtually every component of this process is bad for business. Thus there is a natural temptation to cut corners, underinvest in compliance, or simply look the other way. We can see this in the data. Since 2007, financial institutions have paid more than $50 billion in fines for AML failures. And there are innumerable examples one can point to of gatekeepers prioritizing profitability over their regulatory obligations.

The Surveillance Trilemma

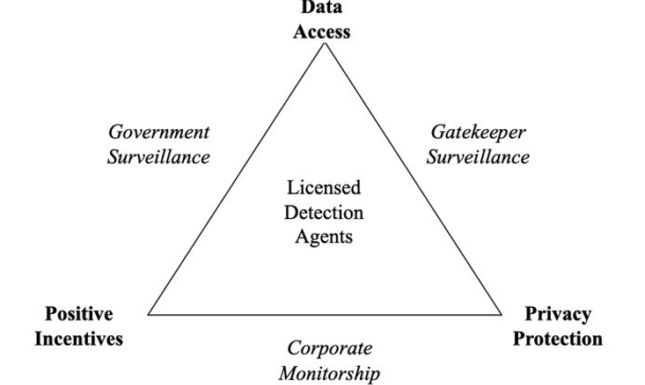

But what is the alternative? One option is to allow government agencies to directly surveil our financial transactions. These agencies would have stronger incentive to detect financial crime. But those incentives would come at the cost of privacy protection. Another option is to lean on the surveillance performed by corporate monitors. This refers to a special type of private actor which independently inspects whether gatekeepers are improving their internal controls. Like regulators, monitors have positive incentives to detect financial crime. But they can generally only view samples of data. Thus, in sum, no existing form of detection is perfect. I refer to this problem as the Surveillance Trilemma:

The Surveillance Trilemma contends that no existing institutional form of detection can feature the following three policy attributes simultaneously: positive incentives, privacy protection, and data access. Each institutional form (in italics) only offers the two adjoining attributes (in bold) while lacking the third. But there is, I contend, another institutional mechanism which can offer all three: Licensed Detection Agents.

Licensed Detection Agents

The paper advocates for the creation of a new class of private firms called Licensed Detection Agents (LDAs). Here’s how it would work. Firms would apply to regulators for a license to act as LDAs. Once that license is obtained, financial institutions would make their data available to LDAs for the purpose of surveillance. LDAs would subsequently monitor transactions and submit reports of suspicious activity to regulators in return for monetary rewards. Specifically, regulators would pay LDAs for each report and provide them with a percentage share of any civil penalties, assets seizures, and/or disgorgements of ill-gotten gains.

By providing monetary rewards, the program would create a competitive market for detecting financial crime. This approach is inspired in part by the demonstrable success of whistleblower incentivization programs. Numerous countries offer whistleblowers percentage shares of civil penalties as an incentive to report misconduct. Empirical evidence suggests these programs are effective at incentivizing reporting. And, crucially, they pay for themselves.

Take, for example, the False Claims Act. The Act allows private persons, known as ‘relators,’ to sue other private persons they suspect of defrauding the U.S. government. If successful, they are entitled to a percentage share of any penalties. Analyzing enforcement data, I find that from 1987 to 2023, the government paid relators approximately $12 billion in rewards in return for more than $70 billion in successfully obtained settlements and judgments.

The LDA Program, too, would pay for itself. The total returns to states would far outweigh the payments made to LDAs for their reports. And the program would offer a solution to our current Surveillance Trilemma. LDAs would possess access to transactional data and offer (relative) privacy advantages. And, crucially, LDAs would not be conflicted. The program would flip the incentive structure of the gatekeeper model, providing LDAs with commercial incentives to perform effective surveillance.

LDAs are not, of course, a perfect solution. There are risks which must be addressed. And the program would undoubtably pose legal complications. But exploring these possibilities, even in an altered form, is worthwhile. Gatekeepers spend billions on compliance – costs which have in some cases been passed on to consumers – with weak results. It is essential, therefore, that both scholars and practitioners continue to examine creative new solutions.