OSINT - Demystifying the Fog of War?

An astonishing amount of information on the Russian invasion in Ukraine is widely available in open sources. This includes events on the ground, often with gruesome detail. Sadly, it has taken a war to reveal the prevalence and evolution of OSINT.

The amount of (visual) information publicly available on the war waged by Russia in Ukraine is unprecedented. The first occurrence of images and (live) footage being shown from within a warzone was in 2003 during the war in Iraq, when the US Army allowed journalists to be embedded with their troops. However, these remained limited and carefully curated images.

A few years later, general citizens began replacing journalists in broadcasting direct images of events out to the world. Especially in the Syrian war that started in 2011, citizens uploaded images as well as video footage from their mobile phones into the public domain. This has been surpassed by the war in Ukraine, where thousands of citizens and soldiers post their accounts of events from within the warzone on a daily basis, mostly via Telegram.

Combined with high resolution satellite images (readily obtainable nowadays), various civil organizations and individuals are able to derive detailed real time insight – which we can view as intelligence – on the happenings in Ukraine. Some examples are:

- two analysts with a military background keep very detailed and documented records of Russian and Ukrainian military equipment losses;

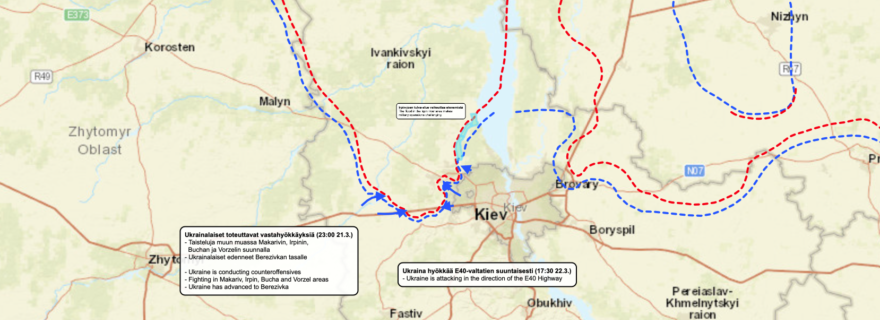

- a number of Finnish volunteers – one of whom is an alumnus of the Leiden University Intelligence Minor – daily map the front positions and movements in Ukraine;

- and importantly, organisations such as Bellingcat are meticulously gathering and documenting evidence of once-invisible human rights abuses, such as the use of cluster munition in residential areas, committed by the Russian army.

Interestingly, established media as well as governments are increasingly recognising and using information collected from open sources by various civil organizations and individuals. As many wars before, the war in Ukraine also appears to be a macabre driver in the development of the structured collection of information from open sources for intelligence purposes, in other words, the development of OSINT. It is thus important to consider - where and how did this begin?

OSINT in times of war

The establishment of the BBC Monitoring Service in 1939 is generally considered to be the first structured collection of information from open sources for intelligence purposes. However, recent research has shown that OSINT practices predate the BBC Monitoring service by 80 years.

For example, in his Yankee Reporters and Southern Secrets, Michael Fuhlhage demonstrates how around 1860, during the outbreak of the Civil War in the US, the structured examination of opponents’ newspapers was a key source of intelligence. Newspaper research in fact became an explicit task of the Army of the Potomac’s Bureau of Military Information, which is widely seen as the world’s first military intelligence service.

Likewise, the first German military Nachrichtendienst (Abteilung III b) was established at the end of the 19th century, with Zeitungsrecherche being an explicit task of one of its sections. They structurally collected numerous newspapers from both France and Russia in search of not only military, but also economic and political information. French counter-intelligence instructions show that they were aware of this covert acquisition of local French newspapers by Germany, and it is evident from French military archives that they also reviewed German and other foreign press.

It took another war for governments to realise how the new technology of radio broadcast could also be a relevant open source. On the eve of the Second World War, the BBC was given the task of structurally listening to and translating foreign broadcasts from all over the world. Two years later, similar efforts in the US led to the establishment of the Federal Bureau Information Service.

Additionally, newspapers were still used throughout WW2 as an important open source of information. As Ben Wheatley details, owing to the fear that using covert means in the Baltics could be a risk to the agreement with the Soviet Union, the Stockholm Press Reading Bureau was set up especially for information from the German-occupied Baltic states.

These efforts procured relevant data, despite the obvious censoring of newspapers and broadcasts in times of war. William Donovan, the founding father of the CIA, emphasized this when he later wrote: “Even a regimented press will again and again betray their nation’s interests to a painstaking observer.”

The Cold War drove the structured collection of information from open sources even further. Significant amounts of newspapers, scientific journals and grey literature were collected and translated, to the extent that an internal CIA document from 1960 discussed a ‘tidal wave of information’ of material from open sources. All this, while the digital revolution was yet to start.

We can now observe how the digital revolution over the past three decades has completely changed the information landscape. However, it again took a war, this time in Ukraine, to demonstrate how OSINT has evolved far beyond the realm of intelligence services.