PKK and Turkey: Time for peace?

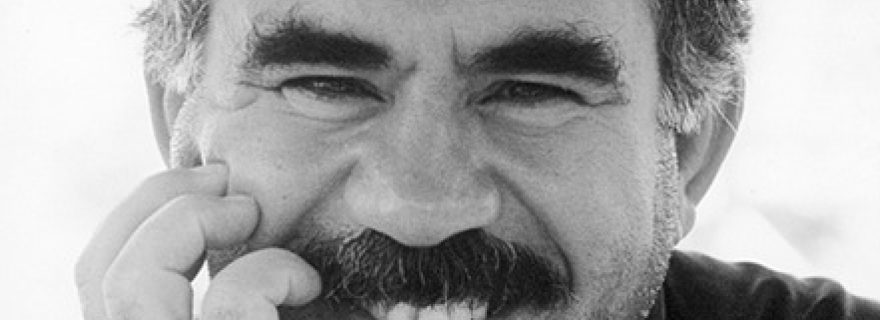

PKK-leader Abdullah Öcalan has called for peace between Turkey and PKK. The following months will show whether Turkey and PKK trust each other enough – at least more than they trust their common enemy Islamic State – to reach a settlement.

The imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan, PKK), Abdullah Öcalan, called for a peace settlement between Turkey and PKK on 28 February 2015. Although it is not the first time he calls for peace, it might be a next step in the peace process since a new regional actor has entered the scene, the Islamic State (IS).

The struggle between Turkey and the PKK started in the 1980’s. Back then the PKK demanded separation from Turkey. This was a reaction to repression of Kurds by the Turkish government, when basically every aspect of Kurdishness was forbidden. PKK was known for its brutal attacks, combining an insurgency with terrorist tactics. A cease fire occurred after Öcalan was captured by Turkey in 1999, often used as an example of decapitation of a terrorist organization. The fighting started again in 2004. From his prison cell Öcalan tried to ease PKK-demands by replacing separatism by autonomy, a term that is still under debate referring to a Kurdish political entity within – instead of next to – Turkey. Although less radical demands would enhance the chance for peace, earlier initiatives have thus far failed.

Why did they fail? Shanna Kirschner states that concerns about future security extend civil wars. For actors to stop fighting they need to trust their opponents; that they do not misuse the opportunity offered by a ceasefire to undermine future security. She argues the level of trust relies on the perception of the adversary, which is based upon the available information about the adversary. Four independent variables influence the perceptions about adversaries: previous conflicts, atrocities, discrimination, and identifiability. Each factor can increase the duration of conflict. Using the conflict between Turkey and the PKK as a case study, she finds that all four are there. Turkish interviewees fear for fragmentation of the Turkish state, are suspicious because of PKK attacks in the past and see the dissolution of the Kurdish nationalist movement as the only guarantee for their future security. Kurdish interviewees do not trust Turkey as a result of the discrimination experienced in the past. Mutual mistrust explains the longevity of conflict between PKK and Turkey.

The essential element of trust is also mentioned by the International Crisis Group in its latest report on the conflict. In the report, the influence of the common jihadist enemy of IS is also emphasized. Speculations of support by PKK-affiliated militia during a Turkish military operation inside Syria late February 2015 might be illustrative of this, although Turkey denies cooperating with the Kurdish militia. The rise of IS might provide the opportunity to bring Turkey and the Kurds (including PKK) together. Recognizing this opportunity, Öcalan’s gesture might be an essential step towards peace. The following months will show whether Turkey and PKK trust each other enough – at least more than they trust IS – for the second step.