Re-entry of High Profile Offenders

One of the main shortcomings in studies on ‘high profile offenders’ is their relatively sample size. One way to overcome this limitation is to study other groups that may be faced with similar experiences.

One of the main shortcomings in studies on ‘high profile offenders’ such as terrorists and others committing lethal offences is their relatively sample size. Studies are often based on a handful of individuals, which makes generalization to a wider population problematic. As opposed to individuals accused of, say, shoplifting, extremely violent offenders are small in number. One way to overcome this limitation is to study other groups that may be faced with similar experiences, grouped together as ‘high profile offenders’.

In an ongoing study on re-entry of high-profile offenders, we combine three groups of offenders that have more in common than you would expect at first sight: Sex offenders, terrorist offenders and homicide offenders. In combining these three groups, we aim to uncover patterns that otherwise remain hidden.

First, the crimes from all three groups – sex offences, acts of terrorism and homicides – generate large-scale societal disturbance. Sex offences, particularly when children are victimized, undermine the community’s perception of public safety. Terrorist acts ranging from the bombing of a building, the assassination of a head of state, the massacre of civilians by a military unit, to the actions of lone extortionists similarly cause widespread scare. The same accounts for homicides, particularly when they take place in a public setting or when they involve “innocent” victims such as women, children or bystanders.

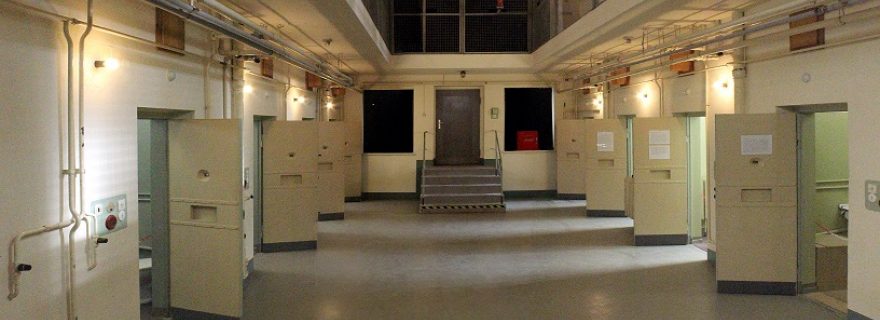

Second, following their offence, all three types of offenders are typically incarcerated for long periods of time, not infrequently, due to their offences, in separate prison wings away from the general prison population. After years of confinement, these prisoners have developed the ability to cope with the prison environment. The opposite is true for life after release, as the consequences of long-term imprisonment come to the forefront. Those sentenced to long-term incarceration are more likely to lose pro-social contacts in the community, and become removed from legitimate opportunities such as work and education after release.

Finally, the re-entry of these types of offenders brings about a new wave of societal unrest, particularly related to the fear that “they will do it again”. This fear is, however, unsubstantiated by actual figures: The lowest recidivism rates are actually found among sex offenders and homicide offenders. To the extent that they re-offend, they typically do so with non-violent crimes such as traffic violations or alcohol/drug related crimes. For the public, such figures remain irrelevant when a convicted terrorist, sex “predator” or homicide offender moves in next door. The question that remains, then, is how we can best ensure a safe transition from prison to society? In a new LUF-funded research project together with Daan Weggemans, we will investigate the best practices surrounding re-entry of this special group of high profile, politically sensitive offenders. Besides the high-impact nature of their crimes, length of confinement and unrest associated with release, they may have more in common than we think.