Reassessing the Role of Youth in Armed Conflict

While the importance of youth empowerment and inclusion in peacebuilding has gained significant traction in policy circles, academic studies capturing the complexity of youth as a transitional demographic with unique transformative potential in post-conflict settings remain relatively scarce.

In 2015, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 2250 on Youth, Peace and Security. Recognizing that “today’s generation of youth is the largest the world has ever known, and young people often form the majority of the population of countries affected by conflict”, the resolution provides the first comprehensive framework seeking to address the unique needs of young people in armed conflict and outlining their capacity for building sustainable peace. Since then, the notion of youth inclusion and youth empowerment has appeared in a plethora of development policies and peacebuilding activities. However, the majority of systematic studies on the role of youth in armed conflict continues to focus on youth as a risk factor, rather than on young people’s potential agency in addressing physical and structural violence.

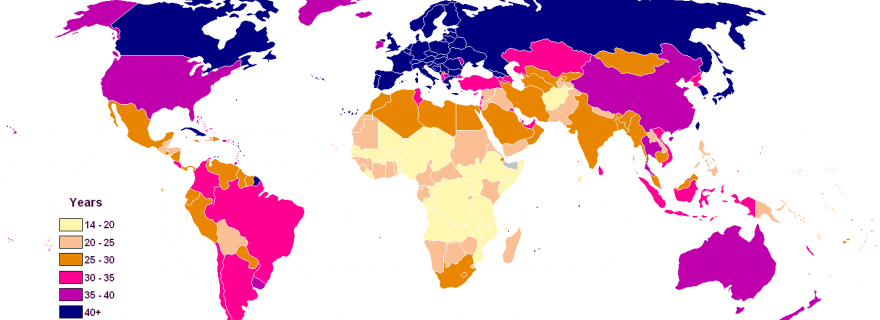

Perhaps the most prominent field of thought linking youth and the onset of organized violence is the youth bulge theory. It links the presence of a disproportionately large youth cohort relative to the rest of the population to an increased risk in the onset of armed conflict, social unrest, violent crime and terrorism. While the theory has been around since the 70s, it has more recently gained new popularity as an explanation for the rise of the Arab Spring and violence in other Middle Eastern and North African countries. It also features quite prominently in policy documents as a key driver of potential future political violence.

Academic support for this theory has been mixed. Several global quantitative studies have found statistically significant correlations between a large youth cohort and conflict onset or recurrence, as well as political instability. Explanations for this relationship range from socio-biological assumptions on the inherent volatility of young men to economic, social and political exclusion causing young people to resort to violence. However, attempts to find support for these underlying causal mechanisms have proven to be more complex. Particularly, macro-level studies into the relationship between age demographics and armed conflict struggle to effectively take into account that “youth” is not one homogenous group and that this identity label primarily indicates a transitional phase in every person’s life. In addition, marginalization of youth can take a variety of forms depending on unique contexts, making it difficult to pinpoint overarching conditions under which the youth bulge theory may be particularly salient.

As such, findings within the youth bulge theory often remain surface level and tend to oversimplify the role young people play in armed conflict. This simplification has painted an unfairly negative picture of youth as a violent risk factor, resulting in a policy panic which has served only to further marginalize this demographic, thus potentially creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Nonetheless, it is important not to dismiss the persistent correlation between youth and political violence entirely. Instead, these findings should be used as further proof of the importance of further investigating the role of young people in armed conflict. Future research on this topic should take great care not to further perpetuate stereotypes of violent young people and should instead focus on their ability to create societal resilience and positive transformation. Good data and systematic research which captures the complexity of youth as a transitional demographic with unique experiences and perspectives will be vital in supporting effective youth empowerment and inclusion in peace efforts.