RISCy Business: How Geopolitics Will Shape the Computing Standard of the Future

Trade tensions between the USA/EU and China has primarily been framed as an issue of current supply chain reconfigurations. With an incumbent Trump II administration, we should look beyond available technologies, and more to emerging tech, considering knock-on consequences for development.

Washington, Brussels and Beijing all appear to have converged on one geopolitical priority: leading the future of computing. The Communist Party of China has emphasised heavy investment in indigenous semiconductor development. Meanwhile the US and EU call for decoupling and derisking from China respectively, with the objective of reducing Chinese businesses’ access to bleeding edge technologies such as extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) machines. The US is determined to maintain its technological edge. The Draghi report raised concerns for EU competitiveness in technological development, with proposals to mine Sweden for critical minerals, somewhat shunning questions over Sámi land usage rights and the environmental impact. However, these geopolitical pressures have not cracked the optimism and collaborative spirit of the engineers and entrepreneurs found in this year’s RISC-V Europe Summit.

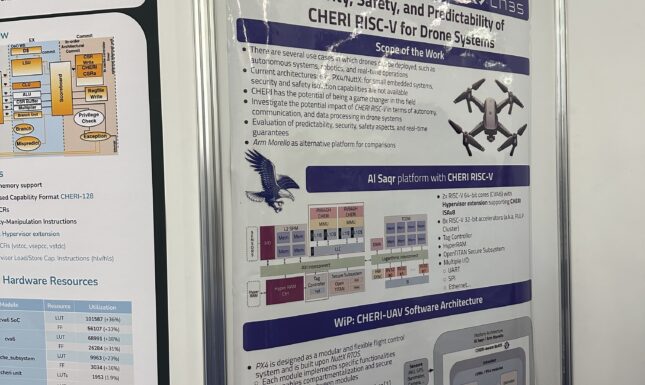

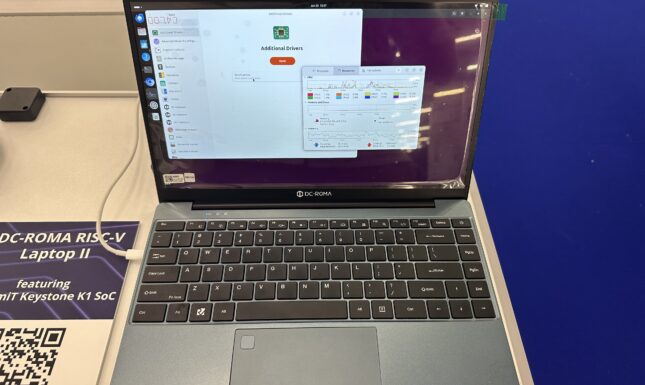

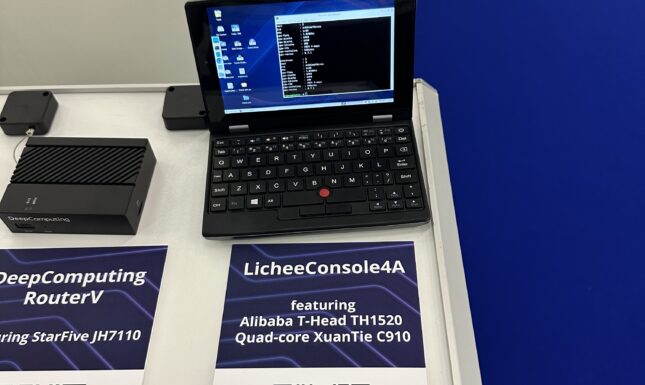

The Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) ISA standard was originally developed by engineers out of Berkley University, expanding to a global consortium called RISC-V International based in Geneva. Simply put, it is a language manual that facilitates the programming of microprocessors and the creation of compatible applications for them. Unlike traditional microprocessor competitors (x86 and ARM), it is an open standard, meaning there is no licence fee to use the instruction set. This choice has facilitated the rapid growth of RISC-V products in a plethora of fields, from drones to laptops, to Internet of Things systems. This standard is available for small enterprises and even individual researchers to design and fabricate their own computer microprocessors, thus making a highly complex and costly product significantly more accessible to the development community. Open source hardware has made several emerging technologies much more financially accessible, from 3D printers to ASIC machines. An estimated 70-90% of all software has its origins in the open source community, showing the ubiquity of it.

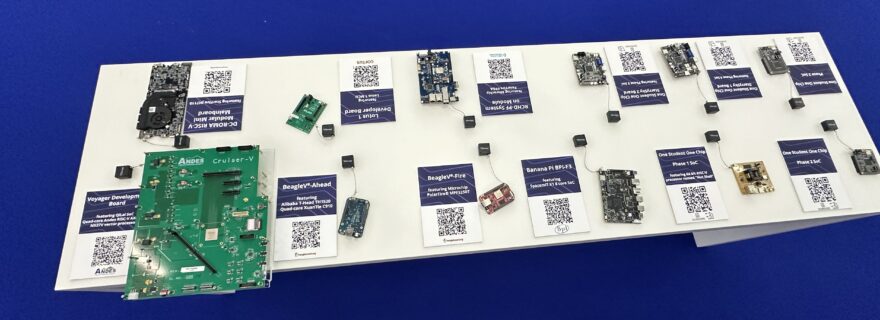

In June I attended this year’s RISC-V summit in Munich. There, numerous product lines were laid out on conference tables to interact with as benchmarks were running in the background (see photos for examples). The attitude amongst participants in the convention hall was optimistic, with consistent positive expressions of international cooperation. Engineers, developers, and businesspeople parlay with each other like close colleagues on a long journey in bringing this market to life. Whereas their home governments would much rather they limit the exchange of knowledge and experiences to their aligned geopolitical camps.

Policymakers mistake RISC-V as any other technology, using conventional tools like export bans as a means to prevent Chinese manufacturers from accessing this standard. US Republican Senator Marco Rubio argued for export control on RISC-V technology to the PRC to maintain its technological advantage, with similar sentiments expressed by the Select Committee on the CCP. Already RISC-V technology has proliferated worldwide, and Chinese products are trading blows with American designs in terms of performance. Unlike EUV technology, outright bans on the sale of this technology will not work. Having talked with some participants at the conference, they were clearly aware of broader geopolitical challenges and were watching developments keenly. Asking a panel of experts about their contingency plans, they were convinced that the open nature of RISC-V would prevent similar technology transfer bans and geopolitical complications.

This overly optimistic attitude is also a mistake. The long arm of the US Commerce Department can hover over these propagating markets. Its decisions and sanctions have extraterritorial effect and can quarantine Chinese RISC-V products. Similar to the Commerce Department prohibiting Nvidia from selling its most advanced GPUs to China, it can use the Commerce Control List (CCL) to ban the sale of RISC-V products outright to the country. However, to mitigate damage to this market, it would more likely involve constructing an evolving list of proscribed entities that cannot be commercially interacted with. Recently, the RISC-V manufacturer Sophgo was banned from using TSMC's advanced node due to their alleged relationship with Huawei. The most considerable impact these measures would have, however, would be shaking investment confidence in future sales to China. Why establish and foster a business relationship with a PRC-based firm if they risk being proscribed at any time? Businesses will tend to actively de-risk from transactions if there is an implicit chance of punitive measures being imposed, raising the barrier to entering the market and reducing their pool of clientele. Putting RISC-V products on the CCL would lead to European businesses being cut off from purchasing potentially superior Chinese solutions or drastically reducing fledgling European businesses from having a reliable client base in the PRC. Given the nascency of this exciting new standard, it is fundamental that RISC-V developers, research foundations, and manufacturers take governmental affairs seriously at this early stage to signal their intentions and expectations with policymakers. The current geopolitical environment is not something this talented community can ignore or wish away. Hence, it requires a clear strategy, diplomacy and tactful negotiation with concerned governmental actors.

There appears to be a perception gap between policymakers and tech developers which academia can help bridge. Security scholars ought to broaden their scope of technological security risks by researching the dynamics, partnerships, and decision-making in developing emerging technologies within this increasingly fragmented geopolitical environment. The CPC is indigenising chip production to sidestep export controls on technology and is building its own microprocessor community by headhunting Taiwanese engineers. This will present new security risks and challenges for policymakers. Knowledge of the RISC-V architecture creates opportunities for identifying exploits and vulnerabilities for economic espionage or cyberattacks. RISC-V processors are projected to be implemented in 10% of edge AI use cases by 2030, and Chinese designers exported 50% of global RISC-V processors in 2022, 5 billion chips, the future of microprocessor design will be increasingly multi-polar. Understanding how latent risks emerge from this technology would allow for the creation of informed policies before it becomes ubiquitous and able to disrupt and cause damage. Researching these emerging risks would be an interdisciplinary task, requiring political science methods, China Studies knowledge, and computer science practice.