The Resilient City

Social cohesion is an important factor for the pace and scope of recovery after crises. The diversity of cohesion of neighborhoods in The Hague implies that tailor-made policies at the community level are required.

More than 10 years after the devastating effects of hurricane Katrina, putting 80% of the city of New Orleans under water, some of its neighborhoods still show remarkable differences in recovery. Half of the neighborhoods saw almost all residents (>90%) return, an important recovery indicator. In other parts of town, only 50% of the addresses are currently inhabited. Although economic capital of the neighborhoods and their residents explains the differences in recovery to some extent, Daniel Aldrich (2012) argues in his influential work on disaster resilience, that ‘social capital’ is a factor that should not be underestimated. His comparative studies, on the US, but also Japan (after Fukushima), show that social cohesion of the population in an affected area is an important factor that influences the pace and scope of recovery.

The relation between social cohesion and resilience in communities is not only important to explain differences in recovery after disasters. In fact, social cohesion (or lack thereof) could also be an important indicator of vulnerability in times of relative prosperity. The data that allow us to identify the extent of cohesion are available at all times. When we can find out which neighborhoods are vulnerable in terms of resilience after crises or disasters, policy makers and crisis managers can take this into account in their crisis preparations, mitigation and prevention plans.

Resilience in The Hague

In her masters study at Leiden University’s Institute of Security and Global Affairs, Dyonne Niehof, supervised by Sanneke Kuipers, mapped the resilience of The Hague neighborhoods based on publicly available statistics. Resilience results from the extent of social cohesion in a community. Aldrich (2012) identifies three dimensions along which social cohesion can be measured: 1) Bonding social capital, such as family ties and tribal or church communities, including the extent to which people relate to a specific neighborhood; 2) Bridging social capital pertains to horizontal ties between people with similar interests, age and activities such as through clubs, sports teams, voluntary work or memberships; and 3) Linking social capital, the extent to which citizens have access to people with political influence (because of their own political activities, for instance). All 48 neighborhoods of The Hague were mapped along a score chart with 44 indicators (14 for bonding, 22 for bridging and 8 for linking social capital) based on publicly available statistics such as surveys and demographic data that were comparable across all cases.

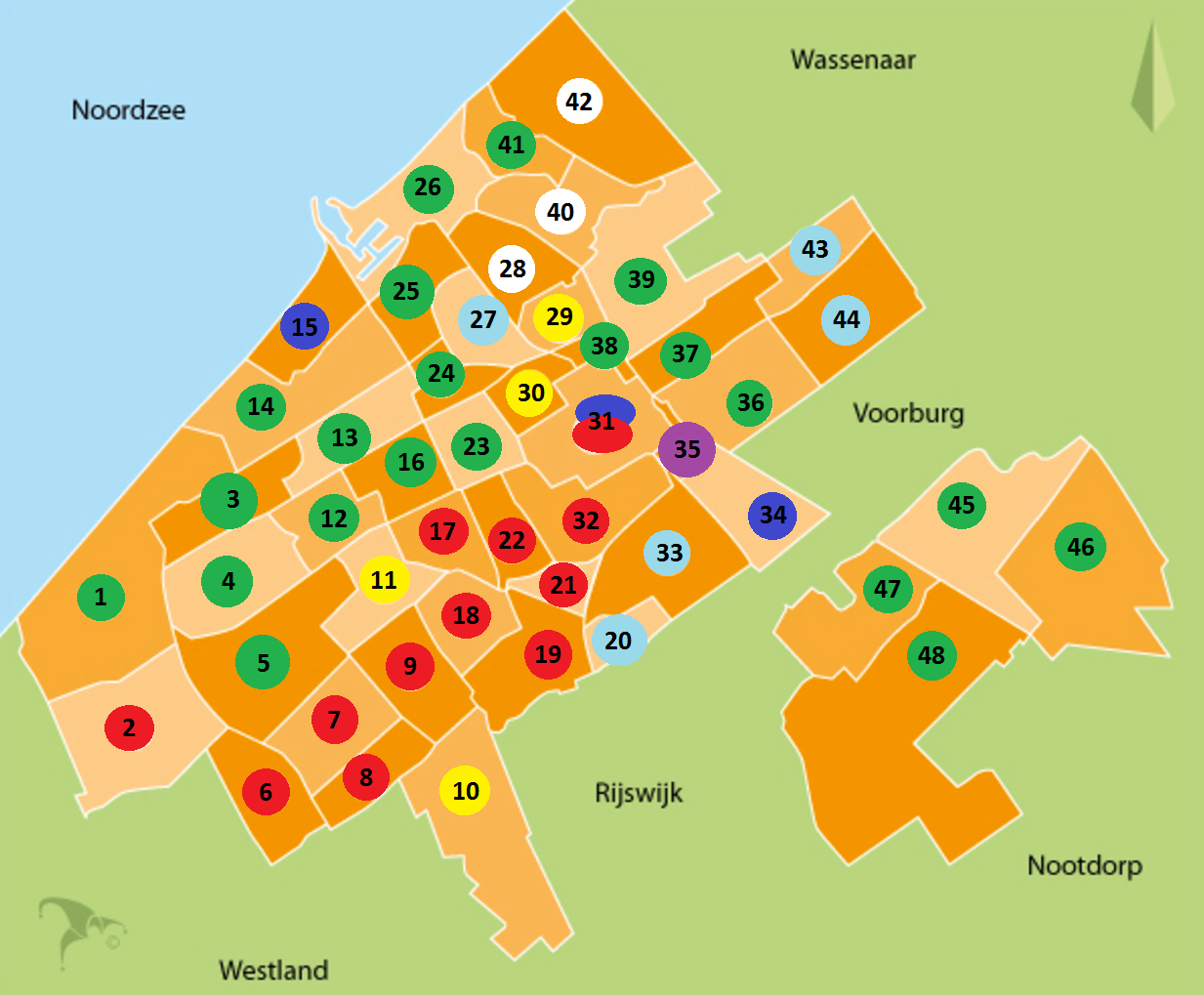

The study produced six profiles. The picture below shows the social capital scores of all neighborhoods in different colors.

- Average-high social capital (green): these (dispersed over different districts) neighborhoods score relatively high on all fronts. Aldrich’s theory leads us to expect that such neighborhoods will experience a relatively rapid and complete recovery after disaster: residents return, houses are repaired, damage will be undone, local economy will rebounce.

- High social capital amidst neighborhoods with a low score (yellow): these communities are interesting because their record stands out in comparison. Their residents have relatively many social contacts and they are happy with their immediate living environment. Studies into underlying causes could generate a spill-over effect that could benefit surrounding neighborhoods.

- High score but very inward looking (dark blue): some neighborhoods are characterized by strong bonding among residents but low satisfaction with their local living environment, high fear of criminality and feelings of distrust towards authorities.

- Low social capital on the rise (purple): one neighborhood justifies its own profile, because of its low scores on bonding and bridging in combination with a positive appreciation of residents for recent changes in the neighborhood and a positive appreciation of municipal politics and authorities.

- Low social capital, period (light blue): these neighborhoods are characterized by limited social contacts among their residents, many of whom appear to be relatively socially isolated.

- Complex mix of factors (red): these neighborhoods score relatively high with respect to both bonding and bridging capital. This high score goes hand in hand with high criminality rates and contrasts with a lack of political ties (low score on linking social capital).

Social Capital Under Pressure

In the near future, a number of developments may put social cohesion in The Hague under pressure. Firstly, the expected population growth from 500,000 to 600,000 inhabitants in 2030. Secondly, the prospected expansion of The Hague Campus of Leiden University, which attracts an increasing number of both Dutch and international students (50% growth) to the city. These students are usually temporary residents and high turnover rates may affect neighborhood cohesion. Thirdly, citizens of The Hague seem to stick with their ethnic group. Active participation and integration between groups could have a positive effect on the cohesion between communities in the city and increase the resilience of the city as a whole.

Increasing social capital

The diversity of the neighborhoods in The Hague implies that tailor-made policies are required at the community level. Aldrich (2012) formulates three recommendations that may help to increase local resilience:

- Local governments can stimulate volunteer work and community service by introducing community currency, such as coupons to be spent on neighborhoods stores and facilities.

- Social capital increases with an increase of activities such as festivals, meetings and markets where residents can meet and socialize.

- Authorities can actively consult residents in a neighborhood and engage them in the design of the public space that surrounds them. A city that actively involves citizens in its planning and policy making will grow socially stronger and increase civic engagement.

During disasters, it is imperative to take social cohesion into account, for instance when planning evacuation. Studies point at the importance of keeping communities together for post-disaster recovery purposes. Most disaster preparedness and planning focuses primarily on the short term, and on physical recovery in terms of infrastructure and buildings. This study shows that the values of social ties should not be underestimated for sustainable recovery.

For more information on this study, please contact Dyonne Niehof. See for the Dutch printed article: Niehof, D. and Kuipers, S.L. (2017) ‘De Veerkrachtige Stad’, in Magazine Nationale Veiligheid en Crisisbeheersing, 4, pp.52-53.

Sanneke Kuipers was invited by BNR News Radio to talk about this blog. You can find the fragment here (in Dutch).

Overview social capital in The Hague. Data source: CBS. 1-Kijkduin; 2-Made en Uithofpolder; 3-Bohemen en Meer en Bos; 4-Waldeck; 5-Loosduinen; 6-Zichtenburg; 7-Bouwlust; 8-Vrederust; 9-Morgenstond; 10-Wateringse Veld; 11-Leyenburg; 12-Vruchtenbuurt; 13-Bomen- en Bloemenbuurt; 14-Vogelwijk; 15-Duindorp; 16-Valkenboskwartier; 17-Rustenburg; 18-Zuiderpark; 19-Moerwijk; 20-Spoorwijk; 21-Groente- en Fruitbuurt; 22-Transvaal; 23-Regentessekwartier; 24-Duinoord; 25-Statenkwartier; 26-Scheveningen; 27-Zorgvliet; 28-Scheveningse Bosjes; 29-Archipelbuurt; 30-Zeeheldenkwartier; 31-Centrum; 32-Schilderswijk; 33-Laakkwartier; 34-Binckhorst; 35-Stationsbuurt; 36-Bezuidenhout; 37-Haagse Bos; 38-Willemspark; 39-Benoordenhout; 40-Westbroekpark; 41-Belgisch Park; 42-Oostduinen; 43-Marlot; 44-Mariahoeve; 45-Forepark; 46-Leidschenveen; 47-Hoornwijck; 48-Ypenburg.