The Rise of Islamophobia and Radicalisation in the Global North

What is the influence of the decline of masculinity and the changing nature of post-industrial societies and economies on the rise of Islamophobia and radicalisation?

Over the last few years, there has been a discernible rise in the nature of Islamophobia and radicalisation, which are not only important issues in their own right but are also notable because of the ways in which they reinforce each other. This is especially the case in the Global North, where the populations of Muslim minorities continue to grow in often-visible urban settings.

As these Muslims endure various incarnations of immigration, integration, isolation or assimilation, based on my social research carried out in UK, supplanted by observations, insights and additional research across the Global North, this blog highlights a range of pertinent issues affecting Islamophobia and radicalisation. It focuses on the intersectionality of these concepts, which to a significant degree reflects on the decline of masculinity and the changing nature of post-industrial societies and economies.

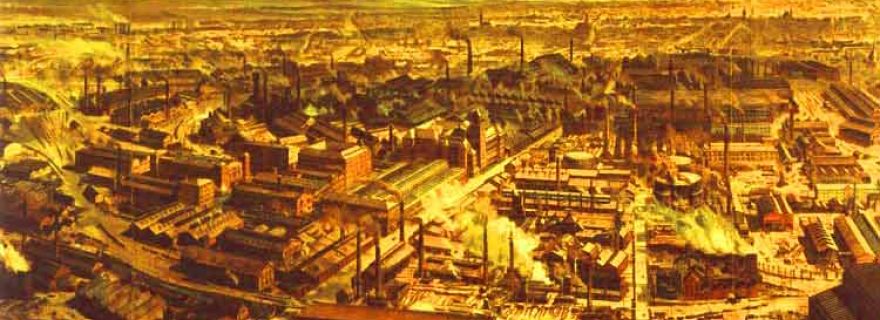

Deindustrialisation, technological innovation and the internationalisation of capital and labour since the 1970s have resulted in significant economic transformations of many countries of the Global North. Economies traditionally reliant on manufacturing have seen a radical decline in domestic investment in this sector, now replaced by a burgeoning service sector economy that has profoundly altered the nature of employment practices. Moreover, this restructuring draws a parallel with geopolitical shifts that have seen the end of the cold war, which, through its own internal logic, suppressed internal political, ethnic and religious mobilisations.

While shades of populism, nativism and conservatism appeared in parts of Europe in the early 1990s, they were largely minimal. The war on terror that began after the events of 9/11 in 2001, however, heralded new binary distinctions between the West and the East. But it also resulted in the re-emergence of xenophobia, wide-ranging anti-immigration sentiment and the securitisation of specific groups; in this case, the constant emphasis on Muslim differences and their ‘lack of integration’ in the Global North.

Numerous transformations faced by liberal democracies now contest traditional approaches to accommodating differences that were once part of a flattening process of mutual tolerance, respect and appreciation. A hierarchical, monocultural and inward-looking political culture and social outlook seeks to replace widely upheld standards. The process disadvantages existing minority groups, but crucially it also isolates majority young men presently facing the prospect of greater job decline in local labour markets. Their female counterparts, having greater qualifications, aggravate the situation in an economy increasingly reliant on service sector employment.

Men faced with limited economic, educational and social status raising opportunities encounter a direct decline in their masculinity. Extreme alienation motivates some to join radical left and right groups, many of which attack ethnic diversity or equality of opportunity for all. This is the realisation of neoliberal globalisation as it affects young men today. In the wake of a global economic financial crash in 2008, societies are more politically, culturally and economically divided than ever, with this reconfiguration occurring with ever greater vigour and uncertainty. The resultant extremism, radicalisation and terrorism is a cry from below, while those who are above are beyond any checks and balances on their activities.

As changes to post-industrial economies lead to greater fissures in all areas of society, Islamophobia, which is the fear or dread of Islam, has a role to play in further isolating Muslim minority men in Western Europe. It also contributes to the anger and dissatisfaction of existing frustrated Muslim men. Radicalisers are all too aware of these social forces in their attempts to recruit the vulnerable and susceptible to extremism, and, in some cases, terrorism. Unsurprisingly, Islamophobia also has a role to play in the radicalisation of angry majority white men, who see faults in the religion of Islam as a whole, painting entire followers of the faith as culpable in the issues that lead the very few, through their limited interpretations, to extremism or violence.

The social, economic, political and cultural forces that have led to the emergence of both Islamophobia and radicalisation have the effect of mutually reinforcing each other. This leads to a cycle of violent action and reaction based on misunderstanding. It is a deliberate misleading of the ill-informed and uncritical angry young man looking to realise their individual identity claims through the aims of the group. Furthermore, rampant individualism driven by neoliberal globalisation fuels the decline of collective norms. Young men at the sharp end of several social challenges, desperately caught between anxiety and ideology, face their perceived collective contestations, in effect, alone.

Insular men turn to the group for solace, comfort and an echo chamber concerned with the demonisation of the other in order to validate the self and invalidate the other. And, so, the cycle continues. Especially in the absence of sound policymaking that fully addresses the structural, cultural, institutional and ideological formations leading to inequality, fear and uncertainty for all.